Bubbles

Bubbles

In the spirit of Christmas, all at Artorius wish you a peaceful Christmas and New Year. Thank you for your continued support and may 2026 be generous in life… and market returns to you.

Summary

At the turn of the year, many look forward to and make bold predictions for the year ahead. We prefer to highlight the similarities (and differences) with the past to provide a potential guide for the risks and opportunities that await in 2026.

Investors may wonder if we are seeing a replay of the technology bubble of the late 1990s. We suggest that although superficially there are similarities, the difference in price action, valuations and earnings backdrop make the environment different.

There are signs of bubble-like conditions in the current environment, but we would suggest that these are limited in scope. The outlook is clouded by elevated valuations in some areas of the US equity market, but valuation risk alone is not sufficient for a US equity bear market.

As long as profits continue to climb and the Federal Reserve continues to cut interest rates (and better than expected inflation data has provided further impetus to cut rates further in 2026) equities are supported.

Bubbles?

“We’re forever blowing bubbles” the timeless refrain from West Ham supporters may reflect the investment outlook at times. Many commentators are convinced that the presence of elevated valuations surrounding the Artificial Intelligence (AI) ‘theme’ is evidence of an investment bubble. Our response is maybe….. but maybe not.

Investment bubbles typically follow a path. Something new and seemingly revolutionary appears and worms its way into people’s minds. It captures their imagination, and the excitement is overwhelming. The early participants enjoy huge gains. These gains attract new entrants (companies) and investors. These new entrants tend to drive equity prices up. These higher prices are then used to justify corporate activity (new investments or mergers) that may subsequently disappoint in terms of actual outcomes or investment returns.

These bubbles repeatedly show up through history: railways in the 1840s, radio and electricity in the 1920s, Japan in the late 1990s, technology in the late 1990s, and finance between 2003-07). This repetition in price action and returns suggests that memories are short, and prudence and natural risk aversion are no match for the dream of getting rich on the back of a revolutionary investment idea or technology that “everyone knows” will change the world.

Bubbles can be good

We might all be fed up with the amount of time spent discussing the potential of AI and the number of column inches given over to speculation about the AI endgame, but this is a trend that isn’t going away in 2026. In fact, it’s only likely to grow, either as AI continues to grow or the bubble, as some see it, deflates.

At the time of writing, all of the top ten stocks by market capitalisation in the MSCI All Country World Index are plays on AI in some form. These include the chip makers powering the revolution, such as Nvidia and Broadcom, and household names like Amazon, Apple and Microsoft, which are at the forefront of AI usage to drive innovation and productivity.

Since the public unveiling of OpenAI’s GPT models in November 2022, OpenAI alone has reached 800 million users in less than two years, a pace that dwarfs the early growth of the internet. Given the rapid pace of growth in AI, there is certainly a chance that growth will moderate.

Ironically, much of the infrastructure that has enabled AI is a result of the vast amounts that investors have ploughed into technology over the last 30 years, including the ‘over-investment’ into the internet in the late 1990s. Whilst equity market losses between 2000-2003 were particularly punishing for investors in technology companies, the economic effect of that investment bubble can be seen as beneficial for many years following.

The technology bubble of the late 1990s (like previous ‘tech’ bubbles including railway (1840s) and electricity (1920s)) can be seen as beneficial bubbles as they financed an infrastructure that aided future economic growth. Sometimes this requires the collective delusion of investing to fund the collective vision of building a new technology. This collective requirement sucks in new capital and investors to fund new projects. Investors may have a fear of missing out (FOMO) on the once-in-a-lifetime technology, which may result in misaligned investment resulting in capital losses.

Looking at the effects of the AI industry on the wider economy, data centre construction in the US is estimated to account for almost all the country’s GDP growth in the first half of 2025. Encouragingly, the longer-term benefits across the economy should prove inherently positive, through higher levels of productivity or lower prices. There will be winners and losers in the integration of AI into daily life and commercial activity. AI now provides access to ‘knowledge’ that previously was in the hands of experts (and normally expensive)… “ask Chat-GPT” is the new ‘Google search’ for information with the ability to structure quite incisive questions. The result is that knowledge has become less expensive to acquire. Of course, knowledge itself doesn’t enable wisdom or judgement. But just as the internet reshaped retailing or office work (no more filing cabinets or typewriters), so AI is likely to drive unimagined changes in the future. And that future feels like it is approaching at an accelerating pace.

We don’t think it’s a replay of 1999

Robert Shiller, a Nobel Prize economist, worked in defining and diagnosing bubbles. In his book "Irrational Exuberance," Shiller proposed a checklist of symptoms. Below are a few examples:

Sharp increase in prices

Overvaluation

Popular stories justifying price action: Compelling narratives, like “new era” thinking.

Tales of significant earnings: Get-rich-quick promises.

Envy and regret among those not invested: Fear of missing out (FOMO).

Media frenzy: High attention, constant reminders of the investment.

It would appear that most, if not all, of these reference points can be checked at the current time.

The current generation of investors and commentators seem to want to portray the current equity market as showing the same characteristics as the 1999 technology bubble. We strongly suggest it is different both in equity price behaviour and investor rationale.

We highlight the price return differences over the one and two years before the peak in 2000 and the current market for the Technology heavy Nasdaq 100 in the US.

Nasdaq 100: comparing the price returns up to March 2000 and November 2025 over the previous 12 and 24 months

| Nasdaq 100 (now) | Nasdaq 100 (March 2000) | |

|---|---|---|

| 12 months | 21% | 122% |

| 24 months | 51% | 266% |

Source: Bloomberg, Artorius

In addition to the price returns, the valuation comparison is also different now compared to the late 1990s, even in the technology sector. Back at the end of 1999, the US S&P 500 technology sector traded on 62x Price to Earnings ratio. Currently the same sector is on 36x. Definitely not inexpensive, but the quantum of valuation stretch is marked in our view. A key difference would also be that many of the leading companies now are highly profitable and have a long history of maintaining elevated profit margins. This is a marked difference to the late 1990s.

Equity Valuations

Source: Bloomberg, Artorius

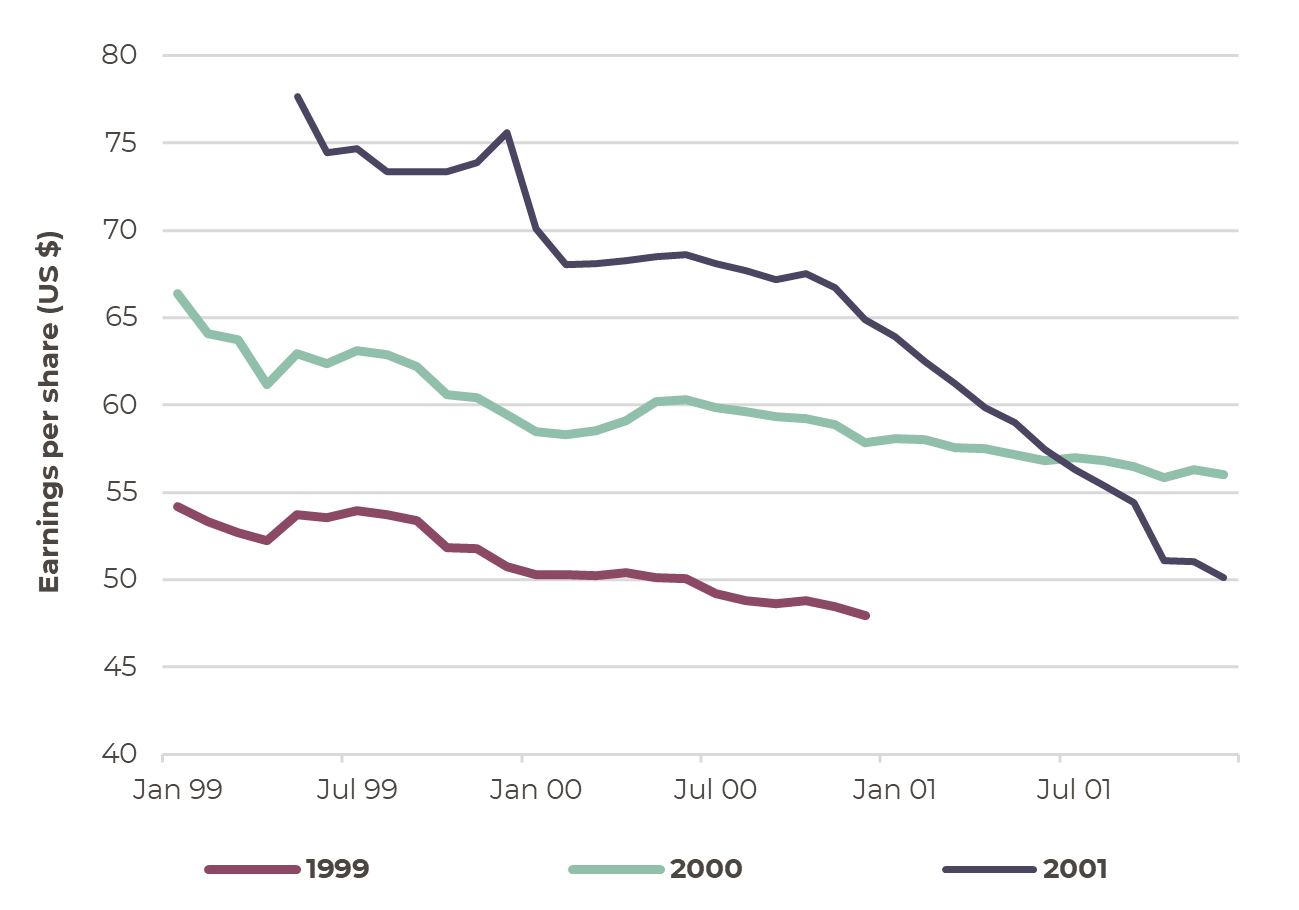

Profitability is a key point. Expectations for US corporate profits are different in comparison with those at the turn of the century. The first chart shows the expected profits for each of the calendar years 1999, 2000 and 2001 and how they changed between January 1999 and January 2002. Even though equity prices were racing ahead in 1999, analysts were reducing their expectations for profits, both for 1999 and for future years. The outlook for profits for 2001 took a sharp turn lower though 2000 and into 2001 as the US economy slowed, even ahead of the terrorist attacks in September 2001.

S&P 500: Expectations for earnings per share (EPS) for 1999, 2000, 2001 …. Drifting lower…. And then sinking fast

Source: Bloomberg, Artorius

The chart to the right shows the expectations for profits for 2025, 2026 and 2027. We are struck that the profits backdrop has been resilient for US equities, despite the lack of good news on the global economy.

S&P 500: Expectations for earnings per share (EPS) for 2025, 2026 and 2027…. Floating higher

Source: Bloomberg, Artorius

Prolonged bear markets (where equities fall by more than 20% on a sustained basis) generally require profits to fall, and that doesn’t seem to be the case at the moment.

Our current analysis of the US equity market suggests that while there may be pockets of overvaluation, the overall market does not exhibit the characteristics of a widespread equity market bubble. But prudence requires that overvaluation is best toned down within balanced portfolios so as to mitigate the impact if we were to be proved wrong.

Bubbles may deflate and other stocks may rise

Looking back to the technology bubble of 1999, between March 2000 and May 2021, US technology stocks fell by 55% with the overall S&P 500 down 13%. Non-technology stocks rose 11% over the same period.

So even if the elevated parts of the US equity market do de-rate and fall in price, despite resilient earnings, it would be consistent with 1999-2001 if other parts of the equity market (both in the US and elsewhere) still provided good returns for investors.

Post the technology bubble bursting in March 2001, non-technology stocks returned an attractive 11% despite technology stocks falling 55% over the subsequent 12 months

Source: Bloomberg, Artorius

Conclusion

At the turn of the year, many look forward to and make bold predictions for the year ahead. We prefer to highlight the similarities (and differences) with the past to provide a potential guide for the risks and opportunities that await in 2026.

Investors may wonder if we are seeing a replay of the technology bubble of the late 1990s. We suggest that although superficially there are similarities, the difference in price action, valuations and earnings backdrop make the environment different.

There are signs of bubble-like conditions in the current environment, but we would suggest that these are limited in scope. The outlook is clouded by elevated valuations in some areas of the US equity market, but valuation risk alone is not sufficient for a US equity bear market.

As long as profits continue to climb and the Federal Reserve continues to cut interest rates (and better than expected inflation data has provided further impetus to cut rates further in 2026) equities are supported.

*Any feedback provided can be anonymous

Important Information

Artorius provides this document in good faith and for information purposes only. All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of Artorius at 19th December 2025 and are subject to change, without notice. Information has been obtained from sources considered reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing report is accurate or complete; we do not accept any liability for any errors or omissions, nor for any actions taken based on its content.

The value of an investment and the income from it could go down as well as up. The return at the end of the investment period is not guaranteed and you may get back less than you originally invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results.

Nothing in this document is intended to be, or should be construed as, regulated advice. Reliance should not be placed on the information contained within this document when taking individual investment or strategic decisions.

Any advisory services we provide will be subject to a formal Engagement Letter signed by both parties. Any Investment Management services we provide will be subject to a formal Investment Management Agreement, which will include an agreed mandate.

Artorius Wealth Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Artorius is a trading name of Artorius Wealth Management Limited.

FP20251219001