Crude Ambitions

Crude ambitions

The year has begun with all the subtlety of a cannonball. Donald Trump’s dramatic seizure of President Nicolás Maduro, his musing over annexing Greenland, and an unapologetically muscular foreign-policy stance have pulled geopolitics back into the limelight. For all of the noise, global bonds have barely flinched, US 10-year Treasuries remain locked between 4.00-4.25%, futures markets are calmly pricing two interest rate cuts in the US during 2026, and oil prices stubbornly refuse to behave as if the world has entered a new age of resource nationalism.

Venezuela’s oil: giant reserves, tiny returns

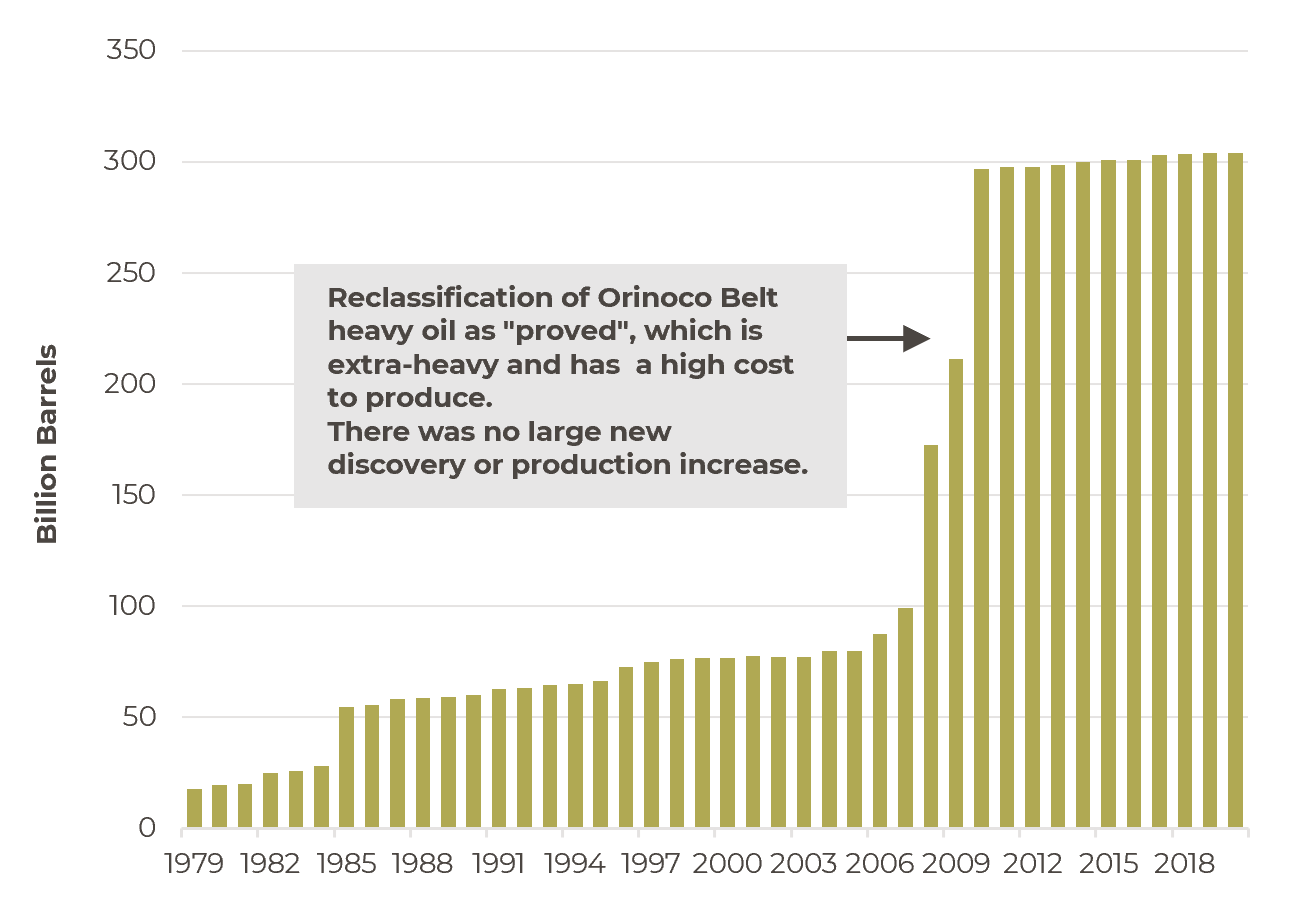

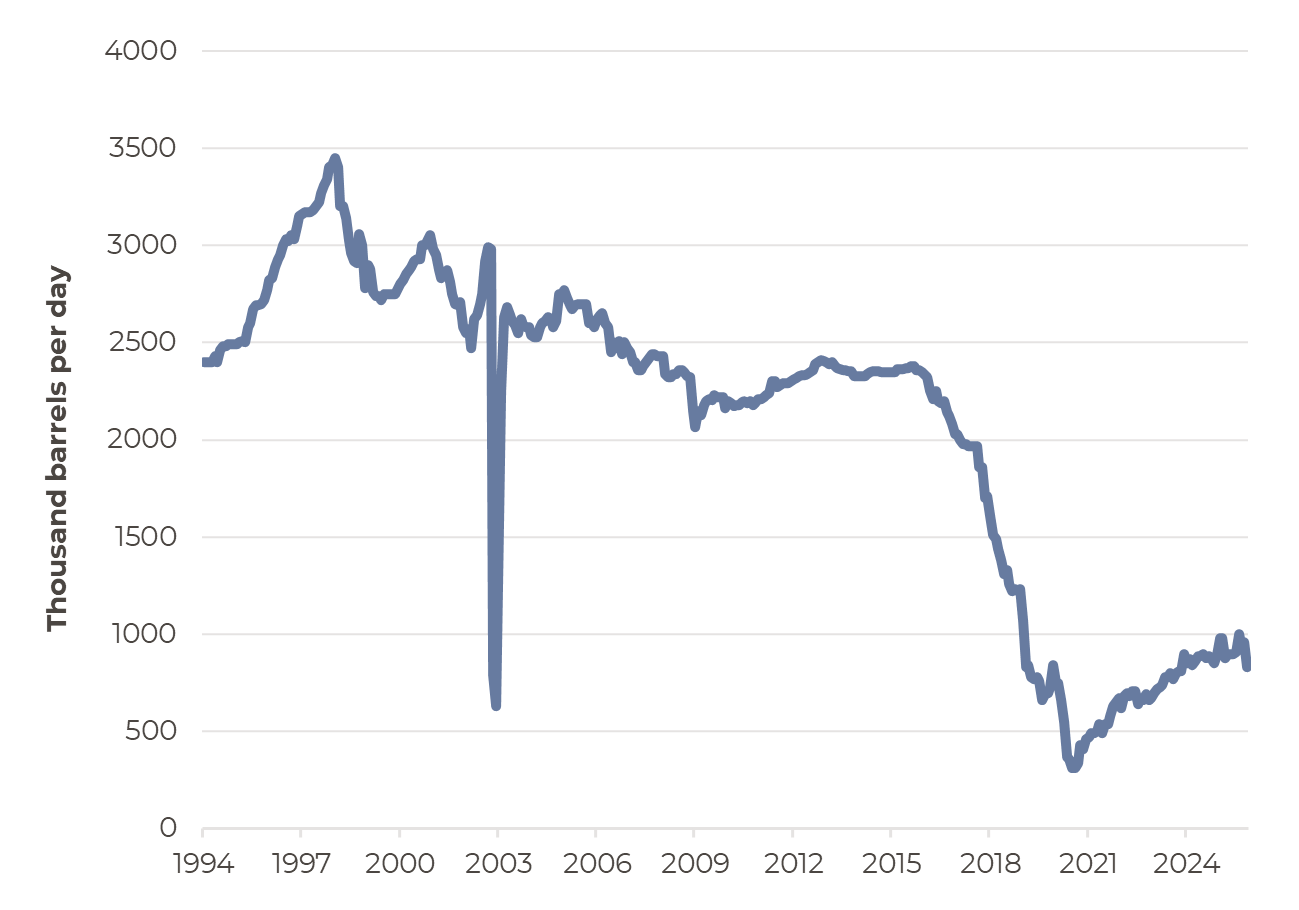

On paper, Venezuela is an energy superpower. Officially it holds around 300 billion barrels of oil reserves, more than Saudi Arabia. In practice, it produces less oil than Libya.

The discrepancy lies in geology and accounting. Much of Venezuela’s oil sits in the Orinoco Belt, a vast expanse of extra-heavy crude with the approximate consistency of refrigerated peanut butter. During Hugo Chávez’s presidency, large portions of this oil were reclassified as “proved reserves”, not because they became cheaper or easier to extract, but because political definitions changed. Production, however, never followed.

Venezuela – reported oil reserves

Venezuela – production of oil

Source: Bloomberg, Artorius

Source: Bloomberg, Artorius

This matters for investors because reserves are not wealth; cash flow is what matters. Heavy crude requires steam injection, specialised refineries, and extensive transport infrastructure - all of which Venezuela lacks after years of underinvestment and mismanagement. Estimates from two leading energy consultancy firms, Wood Mackenzie and Rystad Energy, suggest merely restoring production to 2 million barrels per day would require $10-12bn annually for the rest of the decade, with breakeven prices north of $80 per barrel.

In a world where oil currently trades closer to $50-60, the maths simply does not work.

Big oil has moved on

Today’s oil majors are different beasts: capital-disciplined, legally cautious, and sensitive to geopolitical risk. They have options. According to The Economist, Chevron can drill low-cost barrels in Guyana at under $7 per barrel and Exxon can invest in shale oil or liquified natural gas (alternatives to crude oil). None need Venezuela.

That reality was laid bare in Trump’s recent meeting with oil executives, intended as a show of enthusiasm and instead remembered for one word, “uninvestable.”

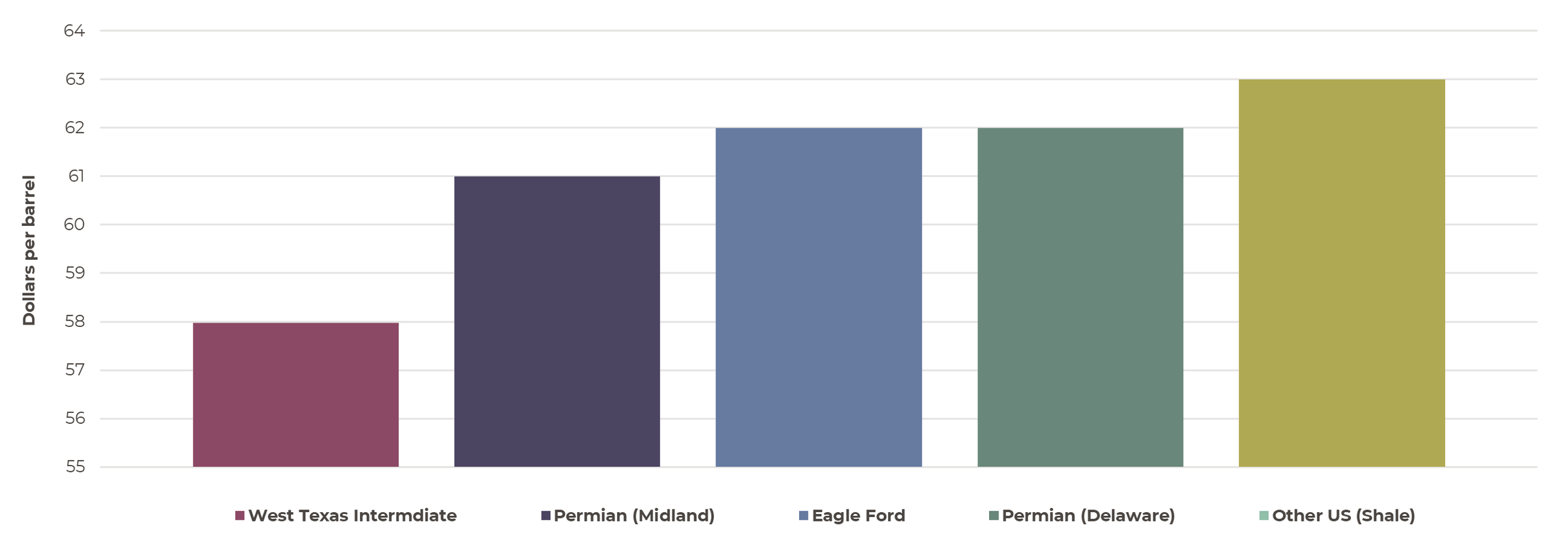

For all the talk of “liquid gold”, oil is cheap - historically and structurally. Fracking has reset the marginal cost of supply, anchoring long-run prices around $60-65 per barrel (breakeven price for US shale) according to the Dallas Federal Reserve. The chart below compares the current West Texas Intermediate (WTI) oil price (shown by the furthest-left bar) with the WTI price levels required for firms to profitably drill a new well across major US shale regions. As shown, the current WTI oil price sits below the break-even price required to justify new drilling activity in each of the geographic and operational regions displayed, indicating that new wells are not economically viable at prevailing prices.

How high does oil need to go?*

Source: Artorius, Dallas Federal Reserve; and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis, Spot Crude Oil Price: West Texas Intermediate (WTI) [WTISPLC], retrieved from FRED, Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis; January 15, 2026.

* Permian (Midland) and Permian (Delaware) refer to the two main sub-basins of the Permian Basin in West Texas and south-east New Mexico, the largest and most productive oil-producing region in the United States. Eagle Ford is a major shale oil and gas formation located in South Texas. Other US (Shale) includes remaining US shale oil-producing regions outside the Permian and Eagle Ford basins.

This has important macroeconomic implications. Low oil prices are disinflationary, and a quiet tailwind for central banks trying to engineer interest rate cuts. Trump’s dream of unleashing Venezuelan supply - were it remotely feasible - would reinforce this low-inflation environment.

The empire strikes back

The rhetoric around Venezuela and Greenland reflects a broader revival of hard-power mercantilism, reminiscent of the Monroe Doctrine. When President James Monroe articulated his 1823 policy, it was presented as a bold warning to European powers that the Western Hemisphere would be closed to further colonial expansion. What followed was not a passive declaration but the foundation of an assertive US hemispheric policy. Over the rest of the 19th and early 20th centuries, the Monroe Doctrine was repeatedly invoked to justify US interventions across Latin America - from diplomatic coercion to military force - to keep European influence at bay and to assert US dominance in its “backyard.” In practice, it became less about defensive sovereignty and more about ensuring that strategic decisions about territory, markets, and resources aligned with US interests.

This doctrine helps explain the action in Venezuela, threats to Brazil, Canada and Mexico, and even the interest in Greenland, which has become symbolic of this dynamic. Its geographic position, near the Arctic and offering the shortest trans-Atlantic routes, makes it strategically vital for defence, surveillance, and influence in the “High North” amid rising competition from Russia and China. The US already maintains a significant military presence there through the Pituffik Air Base, integral to early warning systems and Arctic monitoring. Beneath its ice, Greenland also possesses some of the richest stores of natural resources anywhere in the world. This includes critical raw materials, such as rare earth elements that are otherwise dominated by China, plus other valuable minerals and metals, and a huge volume of hydrocarbons.

Greenland, for all the headlines, risks becoming another chapter in this story. Strategic minerals may matter, but sovereignty by spreadsheet may not deliver prosperity.

The road ahead

The recent capture of President Maduro may reshape Venezuelan politics, but it will not conjure profitable oil projects out of heavy crude and broken infrastructure. For investors, the message is clear. This is not a regime change that changes the nature of returns. Oil remains abundant, capital remains disciplined, and inflation pressures remain contained. The world may feel more dangerous, but markets are - for now - governed less by geopolitics than by the numbers.

Mark Christie

Investment Analyst

*Any feedback provided can be anonymous

Important Information

All expressions of opinion reflect the judgment of Artorius at 16th January 2026 and are subject to change, without notice. Information has been obtained from sources considered reliable, but we do not guarantee that the foregoing report is accurate or complete; we do not accept any liability for any errors or omissions, nor for any actions taken based on its content. The value of an investment and the income from it could go down as well as up. The return at the end of the investment period is not guaranteed and you may get back less than you originally invested. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results. Nothing in this document is intended to be, or should be construed as, regulated advice. Artorius provides this document in good faith and for information purposes only. Reliance should not be placed on the information contained within this document when taking individual investments or strategic decisions.

Artorius Wealth Management Limited is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. Artorius is a trading name of Artorius Wealth Management Limited.

FP20260116001